What does Minnesota’s student debt look like?

After the recent Supreme Court decision struck down Pres. Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan last month, the Biden-Harris Administration worked to open up a new income-driven repayment (IDR) plan— called Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE)—aimed at reducing monthly payment amounts for millions of debt holders and allowing for $0 payments while preventing ballooning interest for single workers earning less than $32,000 a year and for families of four who earn $67,500 or less.

(Borrowers can apply for SAVE here.)

In addition, 804,000 borrowers are eligible for loan discharge—meaning the debt is erased, and credit bureaus are alerted—if they have accumulated 20 or 25 years of qualifying months depending on the loan type.

In Minnesota, that means 13,610 people will have their debt discharged or “forgiven,” according to the Department of Education.

The original loan-forgiveness plan would have canceled up to $20,000 in federal student loan debt for 43 million people.

While Biden’s new SAVE plan will offer much–needed reduced monthly payments for millions of people holding on to student debt—some people well into their 50s and 60s—the striking down of Biden’s original plan by the Supreme Court still will impact people’s ability to spend and save money when student loan payments begin again this October.

This is especially true for debt holders who are people of color or Indigenous (POCI).

Reducing monthly loan payment amounts is critical for low- and middle-income borrowers, and at the same time, we need to address the structural racism still embedded in our country’s inequitable higher-ed financial aid models and the ongoing debt disparities POCI students both take on and continue to hold.

In Minnesota, research shows the people student debt will continue to impact the most are women and people of color—and in particular, Black women with higher-ed certificates or degrees.

Here’s how student debt impacts Minnesota POCI students and what Minnesota must do now to build a more racially equitable higher-ed system—and a more racially equitable Minnesota.

Minnesota ranks among the highest in the country for total percentage of students with student loan debt

According to the most recent Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid Report, an average of 55 percent of Bachelor’s degree recipients from public four-year institutions nationwide graduated with debt and had an average debt level of $26,700 in 2020.

At nonprofit four-year institutions nationwide, an average of 57 percent of Bachelor’s degree recipients graduated with debt and had an average debt level of $33,600.

In Minnesota, however, more students take on student debt than students in nearly every other state. According to the state’s most recent data, 65 percent of all Bachelor’s degree recipients from Minnesota’s public and private four-year institutions graduated with student loan debt in 2020. Their average debt at graduation was $23,767.

While Minnesota doesn’t rank among the highest states for total debt accrued per student, it ranks among the highest in the country for the total percentage of students graduating with debt, according to a recent report from the Institute for College Access & Success.

Only North Dakota and West Virginia ranked higher—by a single percentage point—where both had an average of 66 percent of Bachelor’s degree recipients graduating with student loan debt.

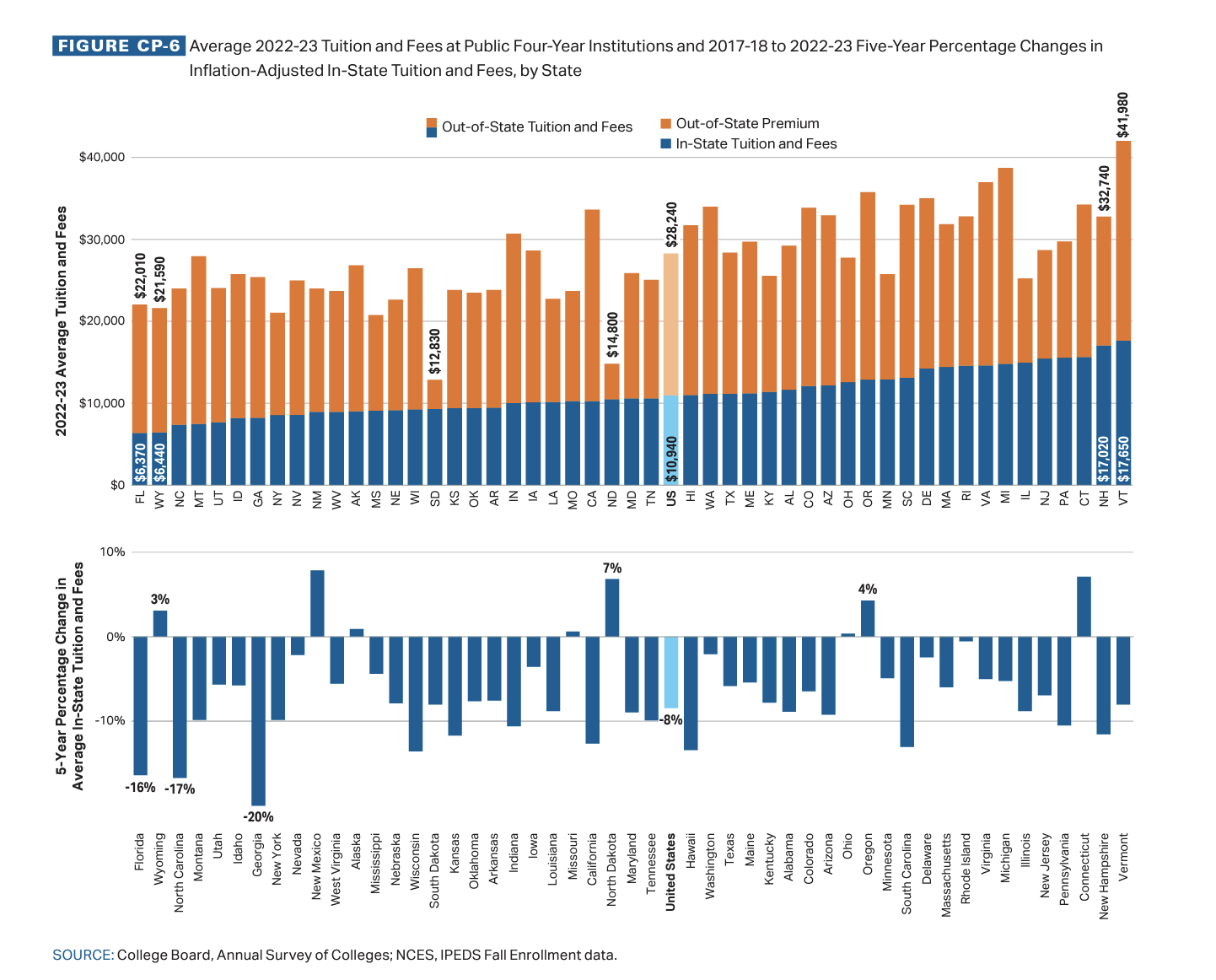

What’s more, Minnesota’s in-state tuition costs at four-year institutions are comparatively high, especially when stacked against other Midwest states. Minnesota ranks 13th highest in the country for in-state tuition costs and fees, and was one of only four states to see tuition increases from 2018-2022, according to Trends in College Pricing 2022.

The impact of student loan debt on students of color and Indigenous students

Black students nationwide—and in particular Minnesota, where we have some of the deepest racial disparities in the country—are disproportionately taking on federal loan debt at a higher rate than any other students and facing deeper pay disparities after graduating with a certificate or degree.

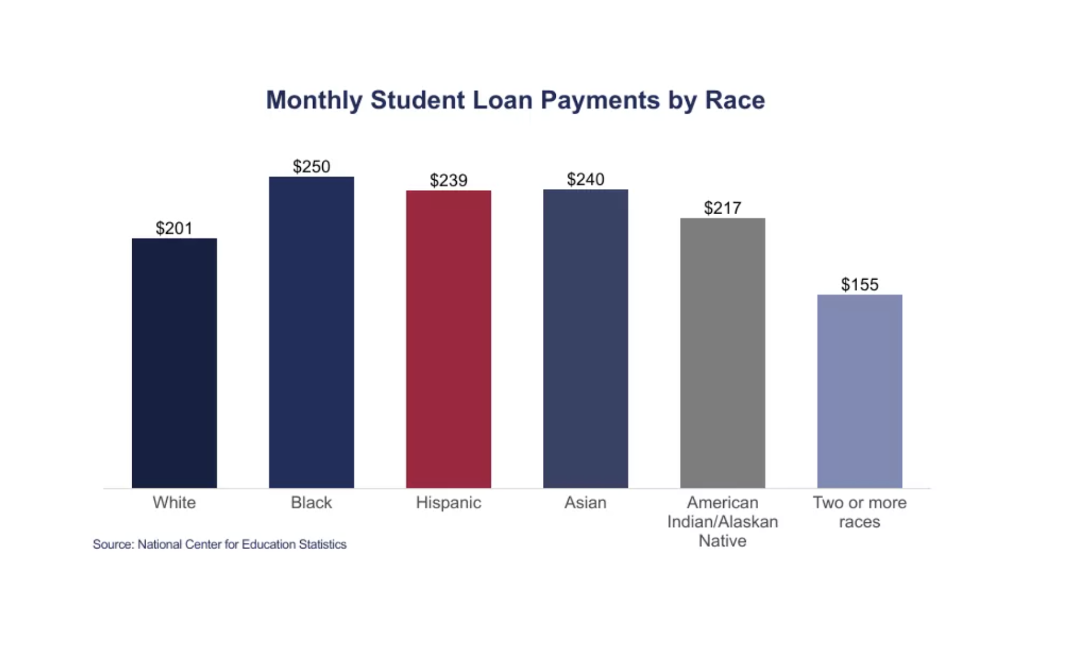

Nationwide, 47 percent of Black students took out student loans in 2020, including at for-profit schools, compared to 36 percent of white students; 25 percent of American Indian students; 25 percent of Hispanic/Latino students; and 25 percent of Asian students taking on student loans.

Black students borrowed an average of $58,400 in 2020 from all higher-ed institutions, which was higher than the average amount borrowed from students who are Asian ($49,100), of two or more races ($43,400), White ($43,300), Hispanic ($41,700), or American Indian/Alaska Native ($36,900), according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

While Minnesota’s student debt data isn’t disaggregated by race, MnEEP research shows that lower- and middle-income Minnesota POCI students are more likely than their white counterparts to take out student loans to finance their tuition costs, fees, living, and miscellaneous expenses, further exacerbating their debt burden and wealth disparities.

Student debt is widening Minnesota’s wealth and gap

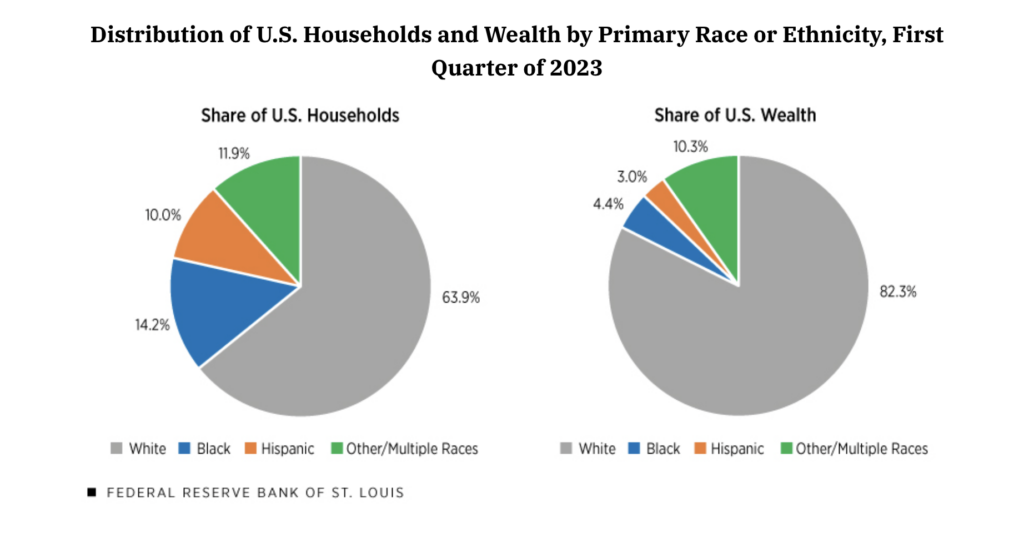

Black students in Minnesota are taking on more student debt—and holding a disproportionate debt burden— due to persistent systemic barriers to wealth. In the second quarter of 2020, the average Black family had 23 cents for every $1 of wealth held by a white family, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

In other words, Black families hold less than a quarter of the wealth of white families and take on an average of 35 percent more debt than white students to obtain a Bachelor’s degree.

Black adults were also more likely to attend for-profit institutions and remain in school for more years than white adults, the St. Louis Fed found. Both factors are related to higher debt levels. (Note: We’re going to look at loan debt from for-profit institutions in an upcoming blog.)

Nationwide, Black women are hit hardest by these disparities. They are the most likely to have student debt, and they have the highest average debt levels. They experience both gender and racial wage disparities, earning 94 cents for every dollar Black men make, 84 cents for every dollar white women make, and 63 cents for every dollar white men make.

The Supreme Court ruling to strike down loan forgiveness will continue to deepen this racial divide if states like Minnesota don’t act swiftly to undo decades of racist practices in higher education and invest in new financing policies and practices that acknowledge and incorporate the social and economic realities of Black women.

What Minnesota must do now

While Biden’s SAVE plan is a crucial step for reducing monthly payments that can often cut into people’s financial stability for decades, Minnesota must support and invest in higher-ed policies that will mitigate debt accumulation and harm going forward while also providing POCI students with degrees and certifications of value that support their career and income goals.

Right now, data shows that the economic return of a college degree is significantly less for Black graduates than their white counterparts and even less for Black women.

While the restoration of the federal debt-to-earnings metric would be a critical step for addressing at the federal level costly programs that do not serve the goals of students—and frankly, harm them— Minnesota must address the debt disparities POCI students face from our public and private institutions now if we want to build a more racially just “One” Minnesota.

Last legislative session, under Governor Tim Walz’s One Minnesota Budget, $650 million was invested into higher-ed for the 24-25 biennium, including the North Star Promise Program (tuition-free for families making less than $80k), funding for tribal colleges, and increases to the Minnesota State Grant, a critical race-equity centered piece of the bill MnEEP worked to shape and advocate for to advance a more racially equitable financial-aid model.

Under the new bill, the State Grant support was increased for students by increasing eligibility for Living and Miscellaneous Expenses (LME) from 109% to 115% of the federal poverty limit, and the state grant eligibility was increased from 120 to 180 credits.

Extending the credit eligibility in the State Grant formula was a crucial first step towards a more racially equitable higher-ed financial aid model.

MnEEP research shows Minnesota POCI students make up a larger share of transfer students, working students, and students in developmental ed courses. The previous State Grant formula that ended grant support at 120 total credits is one of the many ways Minnesota’s financial-aid systems penalized POCI students instead of supporting them in achieving a certificate or degree.

In this upcoming legislative session, the state must look to invest in research and best practices to support reducing Minnesota’s persistent debt disparities—while also working to ensure credentials of value for POCI students and reducing the pay and wealth gap POCI students face.

Long-term debt and persistent pay gaps continue to block wealth accumulation and long-term stability for POCI graduates, even more so as the cost of college rises and POCI students take on a disproportionate share of debt.

Minnesota’s higher-ed institutions, especially its public institutions, have a duty to address these disparities and build solutions, both within their institutions and for the communities they are designed to serve.